Flore Saunois: Words as Matter

Hesitation, procrastination, fear of missing out; it’s not always easy to appreciate the present when the lived experience is full of unlived alternatives. The work of Marseille-based visual artist, Flore Saunois, hangs on this precipice of possibility and traverses the in-between through performance, text, sculpture and intervention. Whether eroded or renewed, material or immaterial, reversed or inversed, Saunois provokes a shift of gaze and a change of perspective in terms of time and matter. Her invitations to this narrow gap, this verge, may appear stylistically subtle, but the effects can be long-lasting.

Words by Reeme Idris, interviewee Flore Saunois

Reeme Idris: I’m curious about the title of your solo show at Art-o-rama (25-28 August 2022) “I would have liked to speak of erosion'“. Is there a link between the text you mention in your interview with Marcelline Delbecq, where the sentence begins ‘I wish I had’(1), and ‘I would have liked to’? There seems to be the acknowledgment of an unfulfilled possibility in the wording of both – would you agree?

Flore Saunois: Although there is no direct link between the two, and they come from different periods in my work, in some ways they do result from the same kind of intention.

The notion of possibility is very important in my work – possibility in the sense of infinite potentialities, myriad versions of ‘that which can happen’. I’m interested in the moment just before one of these possibilities actually transpires since in so doing it inherently invalidates all the others. Just before the ‘point of no return’ where we transition from the virtual (etymologically 'potency') to the actual.

I think it is the irrevocable nature of such transitions that intrigues me: by definition, something that has taken place can never not have taken place. So in my work, I often try to locate myself at this tipping point between ‘what will be’ and ‘what has been’, between the not yet and the already. I try to give it shape or even thwart it.

Perhaps in both of the cases you mention, using the turns of phrase ‘I would have liked to’ and ‘I wish I had’ help to create an alternative expression of this tipping point. It creates a situation in which things can both remain open – with the realm of possibility unscathed – and at the same time take on an existence in the physical world, come to pass …

The apparent failure conveyed by expressions like ‘I would have liked to’, and ‘I wish I had’ – such as regretting something that may not have happened, or that wasn’t achievable – is in fact paradoxically subverted. The failure fails. First on an intrinsic level, because as soon as a phrase is written or pronounced, it takes on a form of existence. Moreover, the context in which I situate these words somehow makes them operational. The way in which they are put to work enables us to play with this ambiguity of a potential 'non-occurrence' that occurs; an occurrence that nevertheless retains uncertain and multiple characters.

Let’s take the example of ‘I would have liked to speak of erosion’, which is actually a specific work as well as the title of the show you mentioned. It consists of a stack of plain paper. A footnote is printed on each sheet:

I would have liked to speak of erosion,

Ongoing performance.

I also saw the work itself as a footnote or legend with respect to the installation as a whole – a performative caption, or a sculptural footnote.

Visitors were invited to take a piece of paper from the pile and thus participate in making it slowly, and almost imperceptibly, diminish. I like the idea that through this very simple gesture (taking with them – and so disseminating – the piece) they actually activate, and are part of, this ‘ongoing performance’ ... leading to the very real ‘erosion’ of the stack over time. And so, in a way, enacting it. ... ‘Something wished for’, and yet ‘something realized’. A way of playing with the performativity of language.

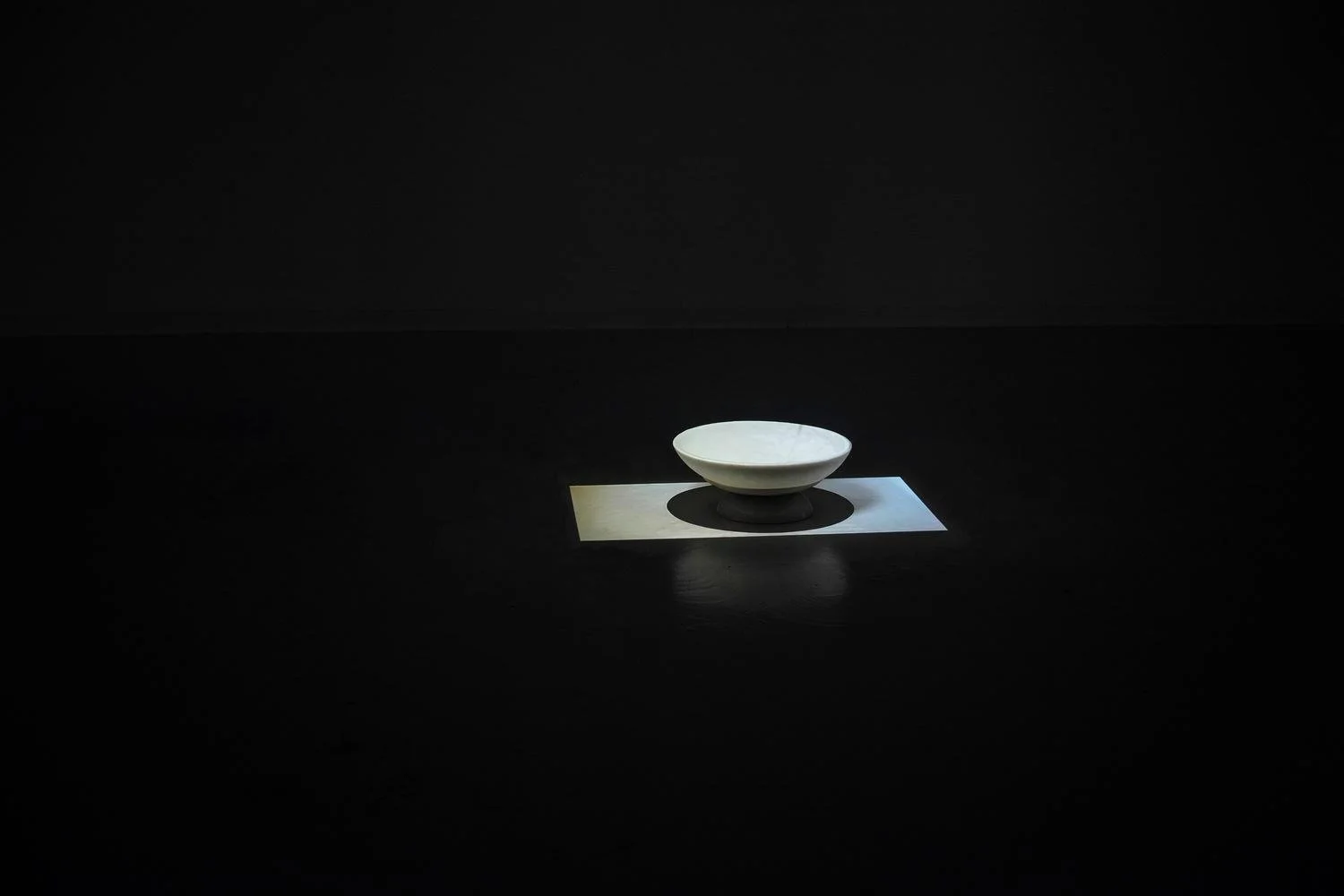

Flore Saunois, Interval (continuous present)

Reeme: Arguably, Interval (continuous present)(2) best conveys this idea of ‘betweenness’, or holding state. The immaterial nature of the water blurs the line between reality, or consequence, and virtual representation. Personally, I experienced a sense of cognitive dissonance when encountering the work. Why do you think this sense of betweenness helps us to question our perception so well?

Flore: For me, playing with perception and representation is a way of questioning our relationship with reality. As you say, in Interval (continuous present) the sense of betweenness lies in the physical and temporal paradoxes that the installation attempts to reconcile. Immaterial water flows into a soap recipient, promising to erode it, to bring about its disappearance. But this potential is never fulfilled, leading to a situation as if always ‘on the brink’. And so the object is plunged into a state of immediacy, the receptacle of a present that is constantly resumed and renewed. Perhaps this particular installation, with the sense of betweenness that it performs and plays with, accentuates a certain consciousness of time … despite the impression of an unbroken flow, we experience the incessant succession of constantly fresh instants ...

I’m thinking of another kind of ‘betweenness’, which perhaps approaches this question of perception differently. In a work like Untitled (folded paper), it is a matter of introducing a slight discrepancy between what we see and what is: the photograph of a piece of paper that was previously folded (in four) is projected (by a slide projector) onto an unfolded piece of paper hanging on a wall. This very simple act, applied to a very simple subject – a folded/unfolded sheet of plain paper – creates something like cognitive dissonance, as you said.

Flore Saunois, Untitled (folded paper)

Here, as I discussed with Marcelline Delbecq, “everything takes place in this gap between an image, its format (or its medium, its means of presentation, or shall we say the conditions of its appearance), and the ambiguity of its nomination (its title, the words placed over it). The space between two states of the same thing. [...] the discord between an object and its representation, between the sign and what it designates. In that way pointing out the little confusion we experience without even noticing … and a fairly mysterious essence of the extant, which ultimately manifests in the slightest everyday object.”

Reeme: I’d like to discuss your exploration of the materiality of language. Could you talk a little about how text became a medium in which to explore the present? I’m thinking of Untitled (a fall without end) and Untitled (the message says nothing) in particular, but also the ‘collision’ of writer and reader.

Flore: When I started out, I would work with text quite a bit, using it as a material in itself, observing what the interactions of the text with a particular material would entail (wondering, for example, what a text for sandpaper would be), or exploring the reciprocal influences between how a text is received (for example reading it in a particular context or position) and the text itself – how they can affect each other. (As in Untitled (the message says nothing), where a text runs in a loop along the walls of the gallery (whose layout of communicating rooms in a ring around a central courtyard is like a circular corridor). Here, the movement is induced by walking through the gallery, and the object of the message, being redefined moment by moment, seems to merge with the object of desire, the driving force pushing the visitor to keep reading.

My trajectory – beginning with text, before gradually broadening my practice to include a wider formal language – perhaps stems from the fact that writing seemed to me to be a medium with which it is possible to capture, very overtly, fragments of the present (a present that is constantly reactivated – a here-and-now that refers both to that of the reader in front of the text and to the exercise of writing, the two colliding at the moment of reading).

Flore Saunois, Untitled (the message says nothing)

But beyond that, it is actually the question of tautology that emerged quite early on; as a method that can address the issues of representation and perception that we discussed before – a way of highlighting more how we perceive than what we perceive, and this through a phenomenon and its slightly shifted twin cohabiting within it. But also as a form which, as I described in a text, “[tautology] allows us to touch the present. At the very moment when we understand that what is said is self-reflective, it holds up a mirror for a brief instant, a spark, letting us contemplate ourselves as we think (at a slight distance which, paradoxically, makes us more intensely aware of ourselves – just like the infinitesimal distance between the object and the subject which, in tautology, is resolved); and for me, this tiny Eureka, this movement, is like directly and immediately accessing a fragment of the present.”

In Untitled (a fall without end), tautology is expressed in the dialogue between the text and the reading device that accommodates it: a text, with no beginning or end scrolls across the surface of a small cylinder that rotates endlessly. By its very action (its obstinate forward motion), the object endlessly realizes and actualizes what it seeks: “a fall without end”. A kind of tautology ‘squared’ ... (and in a way – since by definition a fall implies an end at the moment of impact – it’s again a tongue-in-cheek way of attempting to suspend finiteness ...).

Reeme: I procrastinated while preparing this interview. Talking with Delbecq, you describe reading folded pages as, “A bit like leaving potential intact, or indefinitely postponing the moment of an act it will be impossible to take back.” The element of mischief in your work came to mind – by playing with time and place, the tangible and intangible so effectively, that even this conversation is influenced by it. How do you keep momentum, when suspending it is such a large part of the work itself?

Flore: Yes, “leaving potential intact” is appealing for sure – not least because it is the surest way to avoid failure! But, more seriously, the need to see things actualize, to see them acquire a tangible existence, in reality – even a fragile or precarious existence, at the edge of the imaginary, an existence on the cusp of disappearance, or even a simple intimation/hint of presence – and thus become experiences that can be shared, I think that’s where the momentum lies.

I think what I do try to suspend is something of this irreversibility I talked about previously, something linked to finiteness – meaning chronology (with all the mischief and self-deprecation that such an undertaking obliges). But that doesn’t mean that momentum itself is put on hold. Such suspensions very often rely on movement. Movements like that of a loop, but also the movement of different desires within us.

Reviewed and translated by Clare Poolman.

Images courtesy of Flore Saunois.

With thanks to David Ulrichs PR.

References:

(1) The context relates to an artwork the interviewer (Delbecq) wasn’t sure if she remembered, or had imagined. Saunois, F. (2022). ‘Ornaments of the invisible’. Interviewed by Delbecq, M. Tender surface, monographe, edited by FRAEM, 2022, p. 18. Available here (accessed: 15 September 2022).

(2) Ibid, p. 17, ‘Interval (continuous present), a bowl made out of soap is flooded with light from a video projector positioned above it. The projector continuously plays the video—and the sound—of a trickle of water pouring into a container, such that the bowl seems to be filled with water and perpetually continuing to be filled. Thus at any moment it should (1) overflow and (2) dissolve. Which, because this water is immaterial, will never actually happen. We’re constantly watching an “on the verge of”—on the verge of overflowing, on the verge of dissolving. And yet nothing. So, that imminent instant, ceaselessly renewed, plunges us into a present that’s constantly starting over.’